Prague, 1 April 2025 – Transition from hunting-gathering to food-production (growing of crops and raising of animals) represented a global turning point in human history. New results from archaeological and anthropological research in the Middle Nile Valley show that this innovation was brought to the area by new human groups that arrived in the 6th and 5th millennia BC. This study has just been published in the prestigious journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

Scientists have known for some time that food-production emerged in the northern part of the African continent eight thousand years ago and that from there it gradually spread further south. At first, it was strictly herding of domestic animals of Asian origin. Until recently, however, it was not clear whether livestock herding was adopted by local hunter-gatherers or whether it was brought to the continent by newcomers. A new study by an international team of authors provides the first clear evidence that migrations of new groups was responsible for this change. Using human skeletons from archaeological excavations in southern Egypt and Sudan, the authors show that the earliest herders had a very different biological origin compared to native African hunter-gatherers.

„This study allows us to leave the crossroads at which previous research on the history of Northeast Africa has stopped. It allows us to explore more deeply the interactions between indigenous peoples and the new migrants and to focus on a number of other related questions. Among other things, where these new people came from,“ says Lenka Varadzinová from the Czech Institute of Egyptology at the Faculty of Arts of Charles University, who participated in the study.

Population history hidden in human teeth

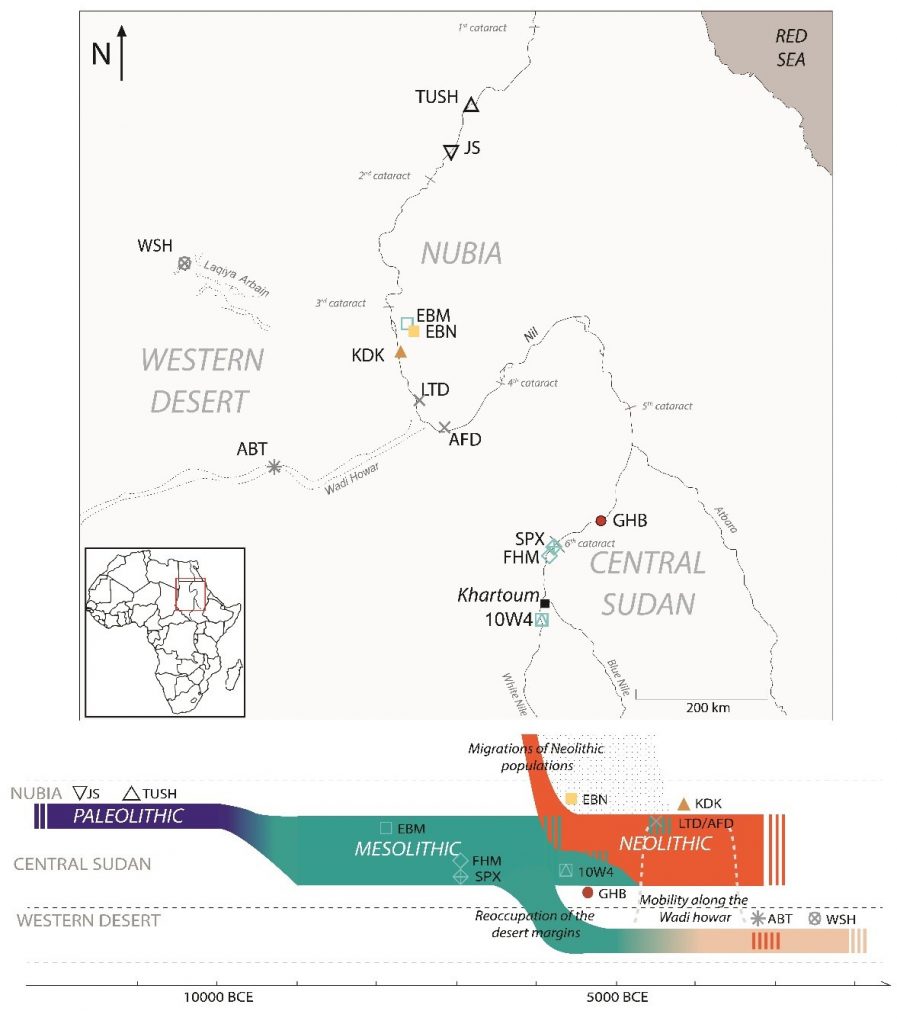

In most of North Africa, it is not possible to investigate changes in ancient populations using ancient DNA because it is not preserved in ancient human skeletons due to the climate. The lead authors of the study, Nicolas Martin and Isabelle Crevecoeur from the University of Bordeaux and the CNRS, therefore focused innovatively on the morphology of the enamel-dentine junction (EDJ) in human teeth, a structure that provides a strong genetic signal. Using X-ray microtomography, they analysed 122 teeth from 88 individuals dated between 16 000 and 5 000 yearsago. They used human remains from 13 sites in southern Egypt and Sudan, ranging from the Late Paleolithic through the Mesolithic to the Middle/Late Neolithic. Among them, skeletons recovered by the archaeological team of the Czech Institute of Egyptology directed by Lenka Varadzinova in the Sabaloka Mountains in central Sudan occupy a prominent position. Two burial sites investigated here – the Sphinx and Fox Hill sites – have provided 15 individuals for analysis, representing over half of all hunter-gatherers analysed in the study.

„The use of enamel-dentine junction analyses marks a methodological breakthrough in the study of ancient population processes, and not only in Africa. This method is applicable wherever teeth have been found on skeletons, regardless of the preservation of ancient DNA. Compared to DNA analysis, this method is also much cheaper and does not destroy human remains,“ adds another co-author of the study, Petra Brukner Havelková from the Anthropology Department of the Natural History Museum of the National Museum in Prague, which has long been involved in anthropological research on the Sabaloka human remains.

The image of migration

The anthropological and archaeological data obtained show that the first herders entered southern Egypt and Sudan along the Nile. In doing so, they quickly replaced local hunter-gatherer groups. At the same time, a different history was unfolding several hundred kilometres west of the Nile. Here, analysis of finds dating back to the Late Neolithic has captured several individuals closely associated with the original indigenous population but who adopted a breeding lifestyle. It is possible that they were relatives or descendants of the last hunter-gatherers driven out of the Nile valley.

„It is not yet clear whether or not the arrival of herders in Sudan was accompanied by conflicts with indigenous groups. In any case, the study provides indications that these herders were not interested in colonizing the regions more distant from the Nile. At the same time, it shows that there were already numerous contacts between the older population, which had remained in the savannahs outside the Nile valley until at least the 3rd millennium BC, and the new Neolithic population along the Nile as early as the 5th millennium BC,“ adds Lenka Varadzinová.

The study reveals a hitherto unknown picture of migration processes along the Nile that occurred long before the formation of ancient Egypt. Once again, it shows that the Nile was one of the key corridors along which innovations and sometimes new inhabitants spread between Asia and Africa.

Study Citation:

Martin N, Thibeault A, Varadzin L, Usai D, Ambrose SH, Antoine D, Brukner Havelkova P, Honegger M, Irish JD, Jesse F, Maréchal L, Osypińska M, Osypiński P, Santos F, Vanderesse N, Varadzin L, Whiting RJ, Zanolli C, Velemínský P, Crevecoeur I. (2025): Enamel-dentine junction morphology reveals population replacement and mobility in the late prehistoric Middle Nile Valley. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences U.S.A. 122 (15): e2419122122. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2419122122 (2025).

More information:

Lenka Varadzinová

Charles University, Faculty of Arts, Czech Institute of Egyptology

lenka.varadzinova@ff.cuni.cz

Tel: +420 602 829 651

Petra Brukner Havelková

National Museum, Museum of Natural History, Department of Anthropology

petra.havelkova@nm.cz

tel: +420 777 692 541

Contact for the main authors of the study:

Nicolas Martin (UMR5199-PACEA, Université de Bordeaux, CNRS)

nicolas.martin.4@u-bordeaux.fr

+33 5 40 00 37 33 / +33 6 65 36 02 94

Isabelle Crevecoeur (UMR5199-PACEA, Université de Bordeaux, CNRS)

Isabelle.crevecoeur@u-bordeaux.fr

+33 5 40 00 33 42 / +33 6 18 24 41 23